课程思政

Exposition-Cause & effect-Education in China

2021-08-11

Education in China

Posted By Stefan Trines On December 17, 2019 @ 5:00 pm In Accreditation and Quality Assurance, Asia Pacific, Credential Evaluation Issues, Education Policy, Education System Profiles, Mobility Trends

Mini Gu, Advanced Evaluation Specialist

Rachel Michael, Manager of Knowledge Management and Training

Claire Zheng, Team Lead

Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

[1]

[1]

Introduction

The speed of China’s emergence as one of the world’s most important countries in international education has been nothing short of phenomenal. Within two decades, from 1998 to 2017, the number of Chinese students enrolled in degree programs abroad jumped by 590 percent to more than 900,000, making China the largest sending country of international students worldwide by far, according to UNESCO statistics [2]. This massive outflow of international students from the world’s largest country—a nation of 1.4 billion people—has had an unrivaled impact on global higher education.

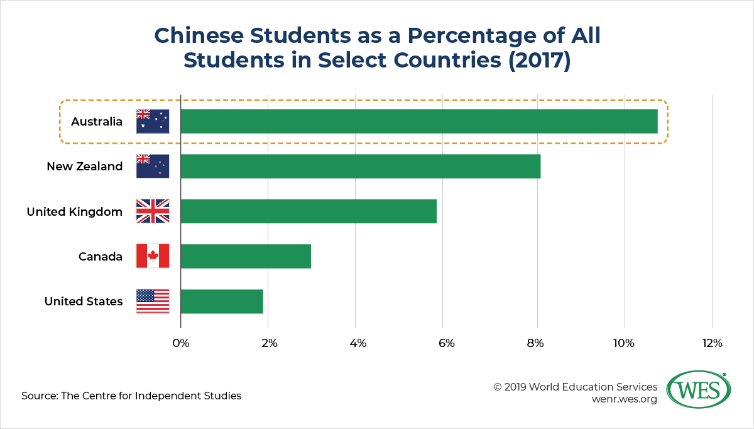

The presence of large numbers of Chinese students on university campuses in Western countries is now a ubiquitous phenomenon. There are three times more Chinese students enrolled internationally than students from India, the second-largest sending country. The expenditures and tuition fees paid by these students have become an increasingly important economic factor for universities and local economies in countries like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom [3]. In Australia, for instance, 30 percent of all international students were Chinese nationals in 2017. These students generated close to USD$7 billion in onshore revenues helping to make international education Australia’s largest services export [4].

[5]

China’s own education system has simultaneously undergone an unprecedented expansion and modernization. It’s now the world’s largest education system after the number of tertiary students surged sixfold from just 7.4 million in 2000 to nearly 45 million in 2018, while the country’s tertiary gross enrollment rate (GER) spiked from 7.6 percent to 50 percent (compared with a current average GER of 75 percent in high income countries, per UNESCO [2]). By common definitions [6], China has now achieved universal participation in higher education.

Consider that China is now training more PhD students than the U.S. [7], and that in 2018 the number of scientific, technical, and medical research papers published by Chinese researchers exceeded for the first time those produced by U.S. scholars [8]. China now spends more on research and development than the countries that make up the entire European Union combined, and it is soon expected to overtake the U.S. in research expenditures as well [8].

Chinese higher education institutions (HEIs) currently pump out around 8 million graduates [9] annually—more graduates than the U.S. and India produce combined. That number is expected to grow by another 300 percent [10] until 2030. Needless to say, this massification of higher education has been accompanied by an exponential growth in the number of HEIs. The BBC reported in 2016 [10] that one new university opened its doors in China each week. Altogether, China now has 514,000 educational institutions and 270 million students [11] enrolled at all levels of education.

What’s more, China’s top universities now provide education of increasingly high quality. Long absent from international university rankings, top-tier universities are now increasingly represented among the top 200 in rankings like those of the Times Higher Education (THE). Fast-ascending flagship institutions like Tsinghua University and Peking University are now considered to be among Asia’s most reputable institutions [12] and appear in the top 30 in both the THE and QS world university rankings [13]. In fact, Chinese universities’ quality improvements and other factors have helped turn China itself into an important destination country of international students from Asia, Africa, and elsewhere.

Rapid Economic Growth

All these developments are part and parcel of China’s spectacular economic growth since the adoption of Deng Xiaoping’s economic liberalization reforms [14] in 1978. No other country in history underwent a more rapid and large-scale process of industrialization than China—an enormous transformation that within decades turned the country from an impoverished agricultural society into an industrial manufacturing powerhouse. Between the 1980s and today, China’s economy expanded at an average rate of approximately 10 percent [15].

Despite this massive growth, China is still classified as a developing country by most measures. For instance, its GDP per capita—USD$9,770 in 2018 [16]—is still comparatively low because of prevailing disparities in wealth distribution in the vast and unevenly developed country. While rising fast, average income levels [17] in China are still comparable to those of Cuba or the Dominican Republic. That said, China in 2011 became the world’s second-largest economy and is on the brink of overtaking the U.S. as the largest economy, if it hasn’t overtaken it already [18]. The country now has the world’s highest number of skyscrapers and the largest airport [19] on the planet.

China’s middle class, likewise, has been growing at a breathtaking pace—a trend that helped fuel the recent leaps in higher education participation and outbound student mobility. By some estimates, the number of urban middle-class households in China—defined as those earning between USD$9,000 and USD$34,000 a year—will increase from just 4 percent in 2000 to 76 percent, or more than 550 million people, by 2022 [20]. Closely interrelated, “China’s urban population skyrocketed from 19 percent of the total population in 1980 to 58 percent in 2017 [21].” What is remarkable about this transformation is that it has thus far not affected political stability. Unlike in other East Asian societies like South Korea or Taiwan, where economic modernization was followed by a push for democratization by newly emerging middle classes, China’s Communist Party (CCP) remains firmly in control.

[22]

Demographic Decline and Other Problems

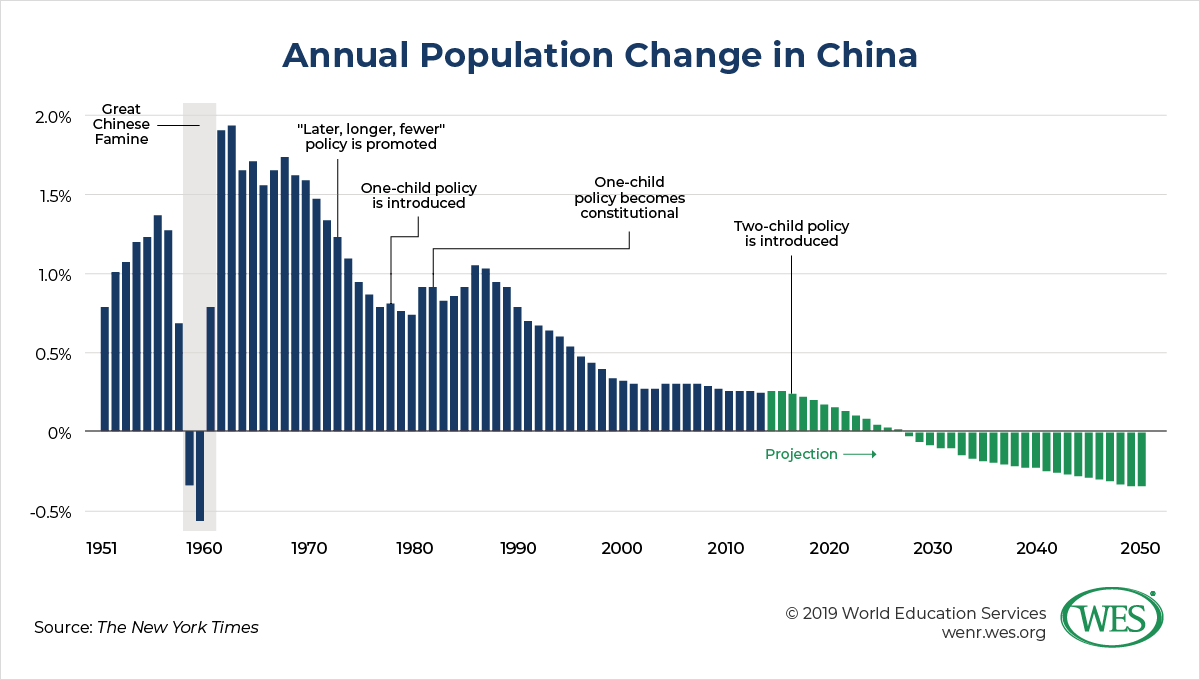

That is not to say that China won’t encounter challenges on its path toward further development. Like other East Asian nations, China is now facing demographic decline and population aging. Despite the abolishment of China’s longstanding and rigid one-child policy in favor of its two-child policy in 2016, the country’s population is expected to begin contracting by 2027 due to factors like decreasing fertility rates, which recently dropped by 12 percent in 2018 [23].

This demographic shift has already resulted in labor shortages with the workforce shrinking by 25 million workers between 2012 and 2017 [24]. On the flip side of this shortage of mid-level technicians, growing numbers of university-educated Chinese remain unemployed [25] or underemployed amid an ever-expanding pool of university graduates [26]. Many educated youngsters now find it increasingly hard to find good jobs, because their skills don’t match the needs of the Chinese labor market and, thus, are not in demand. Except for graduates in highly sought-after fields like engineering or information technology, rising numbers of university graduates end up working in the informal sector or in low-paying jobs [27], potentially a socially destabilizing development.

In response to these problems, the Chinese government is not only pouring massive resources into the modernization of Chinese universities and research institutes, it is also seeking to expand the country’s vocational training system [28]. However, China’s export-driven economy is presently experiencing a significant slowdown [29] amid the trade war with the U.S.—China’s largest trading partner—and a sluggish global economy [30], and other factors. While current economic growth rates still exceed 6 percent, any economic slowdown with negative implications for employment is of great concern to the CCP [31], whose political legitimacy largely rests on delivering increased economic prosperity.

[32]

[32]

Surging Outbound Student Mobility

China’s rapid social changes had an enormous global impact on international education. Both the massification of higher education and the swift emergence of a fast-expanding middle class have created a pool of hundreds of thousands of more affluent education consumers who are able to afford an overseas education, and fueled an unprecedented outflow of Chinese international students.

There are different reasons why so many Chinese students head overseas. For one, many Chinese view an international education as a means of expanding their academic horizons, gaining intercultural skills, and obtaining a top education [33]. There’s a perception among many Chinese that Western universities, particularly U.S. institutions, produce more innovative graduates and critical thinkers than Chinese HEIs.[1] [34]

Academic and financial barriers, meanwhile, are no longer the obstacles they once were, so that more Chinese students can more easily fulfill their academic ambitions to study abroad. In fact, large numbers of Chinese international students, many of whom come from China’s top-tier academic institutions [33], are exceptionally well prepared to enter the best universities in countries like the United States. More than 6 percent of the student body [35] at Harvard University, for instance, is currently made up of Chinese students [36]. Chinese doctoral candidates, likewise, “accounted for 34 percent of all first-year international doctoral students in the United States” in 2016.[2] [37]

While language barriers can be a problem, Chinese students increasingly have the language skills to successfully study in English-speaking countries. There’s now an entire industry of schools that directly prepare students for an overseas education, many of them using English as the medium of instruction or bilingual curricula. According to current statistics [38], China has more than 800 international schools that teach either wholly or partially in English, many of them teaching foreign curricula, such as U.S. or U.K. curricula or the International Baccalaureate.

More and more younger Chinese also study directly at high schools [39] in Western countries. According to a recent report [40] by Sina Education and the Chinese study abroad agency Jinjilie Study, fully 23 percent of China’s international students studied at the upper-secondary level in 2017.

While many Chinese families, particularly those from the less developed, inland provinces, are dependent on scholarships or loans to send their children overseas, the vast majority of Chinese students are self-funded [41] and able to pay for an international education. Despite the high tuition costs and living expenditures in countries like the U.S., 59 percent of Chinese graduates of U.S. universities polled in a recent WES survey [42] expressed satisfaction with the value of the education they obtained in the United States.

And this trend is no longer just confined to households headed by well-paid senior professionals in major top-tier cities. Rising numbers of working-class families are sending their children to study abroad as well [43]. Chinese market research [40] suggests that while most international students come from economically developed regions and tier-one and tier-two metropolises, the potential for greater outbound mobility from lower tier cities is still tremendous.

Another reason Chinese decide to study abroad is to avoid the country’s extremely challenging university entrance test [44], known popularly as gaokao and often referred to as China’s “examination hell.” The test is so stressful that some students commit suicide during the exam [45]. Given the extremely competitive admission procedures of top Chinese universities and the fact that only a minuscule fraction of gaokao test takers gain admission into these schools, an overseas education can be an attractive alternative.

Other students view an international education as an option to better their employment prospects on the competitive Chinese labor market, where a foreign degree was long a golden ticket to well-paid jobs. Studying overseas with the goal of eventually immigrating to Western countries is another motivator. Fully 87 percent of Chinese doctoral candidates studying in the U.S. between 2005 and 2015, for instance, intended to stay in the country after graduation [46]. Chinese nationals, many of them international students on Optional Practical Training visas, filed 296,313 petitions for H-1B visas between 2007 and 2017 [47].

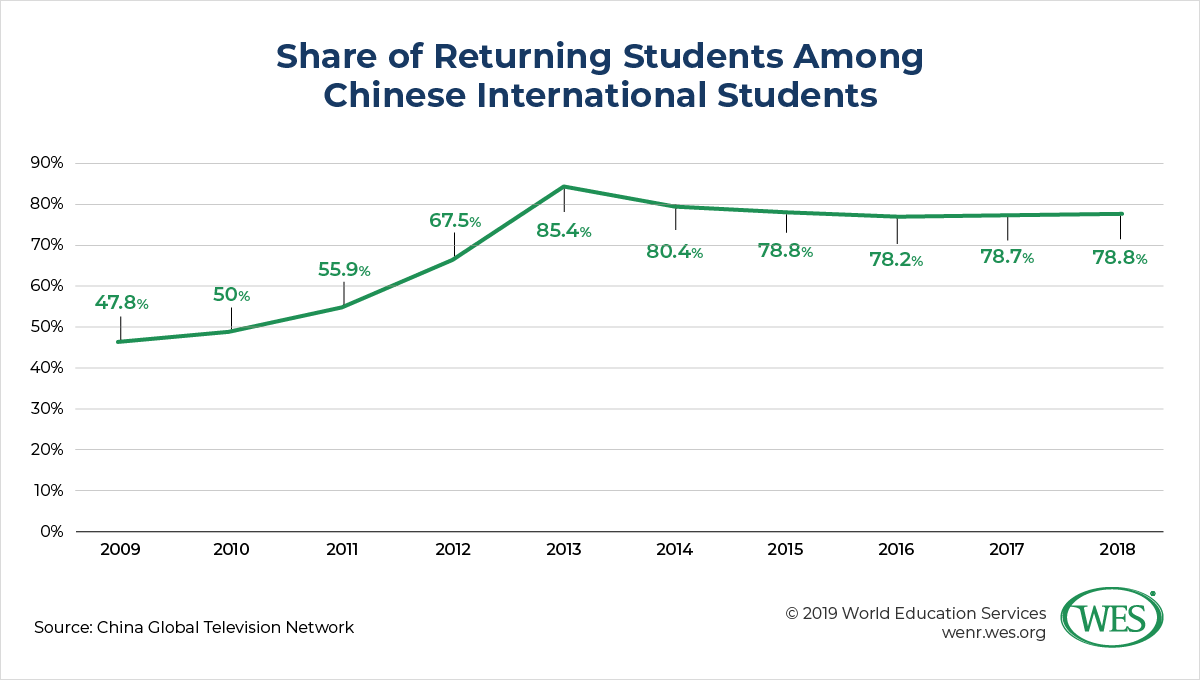

However, these trends are now decelerating; the number of Chinese students returning home after graduation is growing fast. According to ICEF Monitor, “Official government statistics show that 339,700 Chinese students went abroad during 2011, with 186,200 overseas graduates returning to China that same year. In 2016, 544,500 Chinese students went abroad while 432,500 returned from overseas study [48].” Between 2009 and 2018, the percentage of students returning home after graduation jumped from 48 percent to 80 percent [39].

[49]

[49]

Tightening visa and immigration restrictions in the U.S. are one reason for the slowing of China’s brain drain. But perhaps more importantly, there are now more well-paid employment opportunities available in China’s growing economy. Not only is the government incentivizing Chinese academics to return home by offering funding and research opportunities [50], there are also ample opportunities for STEM graduates in China’s booming tech sector. As Bloomberg journalist David Ramli writes in the Taipei Times [51]:

“US-trained Chinese-born talent is becoming a key force in driving Chinese companies’ global expansion and the country’s efforts to dominate next-generation technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. Where college graduates once coveted a prestigious overseas job and foreign citizenship, many today gravitate toward career opportunities at home, where venture capital is plentiful and the government dangles financial incentives for cutting-edge research.”

That said, far from all returning students find golden opportunities back home. Outside a few economic sectors, a foreign degree has largely lost the sheen and earning power it once had, especially if graduates return without work experience. Not only is the labor market flooded with internationally educated graduates, the increasing quality of graduates from China’s top universities has also evened out the playing field, diminishing the return on an expensive international education. Consider that in 2017, internationally educated graduates earned on average only USD$71 more per month than domestic graduates and may have difficulty finding jobs because of stiff competition and weak social networks [52].

These developments cast doubts on the future scope of outbound student mobility from China, especially since the size of China’s college-age population is projected to shrink by some 40 percent [53] between 2010 and 2025. Given the overdependence of many Western universities on tuition fees paid by Chinese students, the prominent international education scholar Philip G. Altbach recently warned [54] of a coming “China crisis” in global higher education amid domestic transformations in China and rising political tensions between China and Western countries. In fact, after averaging 19 percent annually over the past decades [55], annual growth rates in outbound student flows, while still high, have in recent years already fallen by several percentage points. [56]

Global Outbound Numbers

After decades of relative isolation under Maoist rule and the closure of Chinese universities during the Cultural Revolution, outbound student mobility from China took off in the last two decades of the 20th century. In 1998, the earliest year for which UNESCO provides data on outbound degree-seeking students, China was already the largest exporter of international students followed by South Korea, Malaysia, India, and Germany. In that year, there were slightly more than 134,000 Chinese enrolled in degree programs abroad, compared with about 62,000 South Koreans (UNESCO estimation [2]). Since then, the number of Chinese students has grown by 592 percent to reach 928,000 in 2017—a number that represents 17 percent of all international degree students worldwide. More than a third of these students are enrolled in the U.S., the most popular destination country by far. The next popular destination countries in 2017 were Australia, the U.K., Japan, and Canada.

The U.S. Remains the Top Destination Country Despite Slowing Growth

According to the Open Doors data [57] of the International Institute of Education (IIE), China in the 2009/10 academic year overtook India to become the largest sending country of international students in the United States. Since then, the number of Chinese students has spiked to 369,548 in 2018/19, which means that close to 34 percent of all international students in the U.S. are now Chinese nationals.

Like most international students in the U.S., Chinese students are concentrated in New York and California, but they study on campuses all over the country—44 percent of the international students in Ohio, for instance, are Chinese, according to IIE [58]. Forty percent of Chinese students are enrolled in undergraduate programs, 36 percent in graduate programs, and close to 5 percent in non-degree programs; 19 percent pursue Optional Practical Training. Computer science and mathematics, engineering, and business are the most popular majors among this student population.

Studying in the U.S. is a dream of many Chinese youngsters. However, while the number of Chinese students in the U.S. increased by 1.7 percent in 2019, the growth rate of enrollments has slowed noticeably in recent years. Consider that growth used to average 20.9 percent between 2009/10 and 2014/15. This slowdown is ringing alarm bells for U.S. universities, some of which are now witnessing double-digit declines in Chinese student enrollments. To mitigate the effects of this trend, the University of Illinois’ Gies College of Business went so far as to take out a USD$61 million insurance policy to financially protect itself against the potential loss of Chinese students [59].

There are several factors that are likely to contribute to this stagnation. For one, domestic developments in China outlined above are bound to have a significant impact. But it’s also the rising political tensions and trade war between the U.S. and China, as well as new visa restrictions imposed by the Trump administration, that drive the slowdown. The geopolitical conflict ripples through U.S. higher education in several ways. For example, in 2018 the U.S. government shortened the length of student visas for Chinese graduate students in aviation, robotics, and advanced manufacturing from five years to one year, citing concerns about intellectual property theft and Chinese espionage [60]. A report [61] by the White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy accused the Chinese government of infiltrating U.S. companies and university campuses to transfer technology, intellectual property and know-how.

Accounts of stricter vetting and denials of Chinese nationals’ student visa applications have already become increasingly common. In one recent incident, nine Chinese students were denied entry in Los Angeles and deported despite holding valid visas [62]. More draconian screening procedures are under consideration; [63] White House advisor Stephen Miller is reportedly even proposing to stop issuing visas to Chinese students altogether [64]. Current plans [65] to further restrict eligibility criteria for OPT and H-1B visas are all but certain to have a detrimental effect on student inflows from China and other countries.

The Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE) has responded to these developments by discouraging its citizens from studying in the U.S., stating that U.S. policies “hurt the dignity of Chinese students.” The ministry noted that the “visa applications of some Chinese hoping to study in the United States have recently been restricted, with an extended reviewing process, shortened validity periods and increased rejection rate, which has affected their plans to study in the United States, or the completion of their study there [66].”

These tensions have left an impression on Chinese students and causes growing numbers of them to turn their back on the United States. Consider that 87 percent [67] of high school college counselors in China surveyed by Amherst College in 2019 stated that the U.S. government’s “unpredictable policies toward Chinese students” are the most important factor for Chinese students and parents. Xiaofeng Wan, associate dean of admission and coordinator of international recruitment at Amherst College, described these sentiments as follows: “The constant anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Trump administration, talk of banning student visas for all Chinese students and suggestions that ‘almost every [Chinese] student that comes over to this country is a ‘spy’ don’t resonate well with people on the other side of the globe. The constant stream of negative news has exacerbated the growing worries about the wisdom of the U.S. as a study destination [67].”

In another survey, 52 percent [68] of Chinese students agreed that “not being able to obtain a job in the United States postgraduation would prevent them from pursuing business school there.” That said, an equally important factor are fears related to gun violence and the highly televised mass shootings in the U.S.—an issue that ranks high in many surveys of Chinese students. Sixty-seven percent of Chinese international students polled by WES in a recent survey[3] [34], for instance, stated that they were worried about gun violence. One student was recently apprehended at the airport because he had a bulletproof vest [69].

All these developments cast doubt on the future growth of Chinese student enrollments in the U.S., particularly since other countries like Australia and Canada are actively vying for Chinese students. Although it may sound almost like a cliché by now, U.S. institutions will have to brace for potential downshifts in international student flows from China.

Recruitment Agents in China

According to a recent WES survey[4] [34], more than half (54 percent) of Chinese students come to the U.S. with the help of recruitment agents who assist them with preparing applications and essay writing. By some estimates, there are 10,000 registered and unregistered agents in various Chinese cities. Many of these agents provide prospective international students with valuable services, such as identifying appropriate institutions and programs, submitting transcripts, or sometimes even providing training for language tests. Some students come from “small centers in rural parts, their family doesn’t speak English, and they’re making one of the largest transactions of their life…. They’re spending a lot of money and a huge amount of faith. They need to talk to someone to get information, and schools aren’t set up to provide [70]” this type of counseling.

On the downside, some of these agents take advantage of students and charge exorbitant fees. What’s more, unethical practices, such as the falsification of records or ghostwriting of essays, can also be a problem. In 2016, for instance, China’s largest private education company, New Oriental, was sued in the U.S [71]. for submitting fraudulent college applications after a Reuters investigation alleged that it had engaged in “writing application essays and teacher recommendations, and falsifying high school transcripts [72].” Amid such reports, some U.S. institutions are now relying on video interviewing [73] when evaluating Chinese applicants. It should be noted, however, that such problems are hardly confined to China. Australia’s government, for instance, felt compelled to establish a National Code of Practice for Providers of Education and Training [74] to rein in corrupt agents, fraud, substandard admission standards, and questionable recruitment practices by education providers seeking to cash in on the boom in international student mobility from China, India, and elsewhere.

Australia

Australia’s position as the third most popular international study destination worldwide is to a large extent owed to the influx of Chinese students. Between 2002 and 2018, the number of Chinese enrolled in Australian institutions spiked by 434 percent, from 47,931 to 255,896, according to the Australian Department of Education [75]. These statistics, which include students in tertiary education, vocational education, language training, secondary education, and non-awards programs, indicate that 30 percent of international students in Australia are Chinese. When looking at tertiary education alone, that percentage is even higher—38 percent.[5] [34]

Several Australian universities are now said to have “higher proportions of international and Chinese students than any university in the entire United States [76].” More than 50 percent of the international student body of the University of Sydney, the most popular university among Chinese students, is reportedly made up of Chinese nationals. The scale of these proportions has raised alarms about financial risks due to an overreliance on tuition fees from Chinese students. There are also concerns that this trend has negative implications for academic quality. As Australian economist Salvatore Babones has noted [76], “Australian universities routinely compromise admissions standards to accommodate international students” and use “preparatory programs for students with lower English language test scores … as a … work-around for international students who do not meet admissions standards.”

Another concern is that Chinese students shape academic discourse in Australia in a negative way with controversies over topics like China’s territorial disputes playing out on campuses, sometimes resulting in academic self-censorship to avoid conflicts.

Beyond that, there are fears that China’s state-sponsored Confucius Institutes—Chinese culture and language institutes housed in universities—threaten academic freedom and undermine Australia’s security by putting sensitive research and intellectual property at risk. The Australian Security Intelligence Organization in 2018 issued a sharp warning related to these concerns. It noted that when “anyone wants to have any kind of public discussion [on human rights or Tibet or Taiwan] a lot of the instigators for counter-reaction to that, and the shouting down of anyone who wants to talk, come from people associated with … Confucius Institutes [77].” The state of New South Wales in 2019 already closed one of the 14 Confucius Institutes in Australia [78]. Likewise, the Australian government recently set up a University Foreign Interference Taskforce [79] to address Chinese influence on campuses, while some universities are reassessing their research collaborations [79] with Chinese partner institutions.

It remains to be seen how these developments will affect student mobility from China. There are currently few signs that student flows to Australia will recede—the number of inbound Chinese students grew by 4 percent between August 2018 and August 2019 [80]. However, that growth rate is seven percentage points below that of the year before, and there’s the potential that rising diplomatic tensions and domestic developments in China could significantly deplete student inflows, and with it, the revenues of Australian institutions.

[81]

[81]

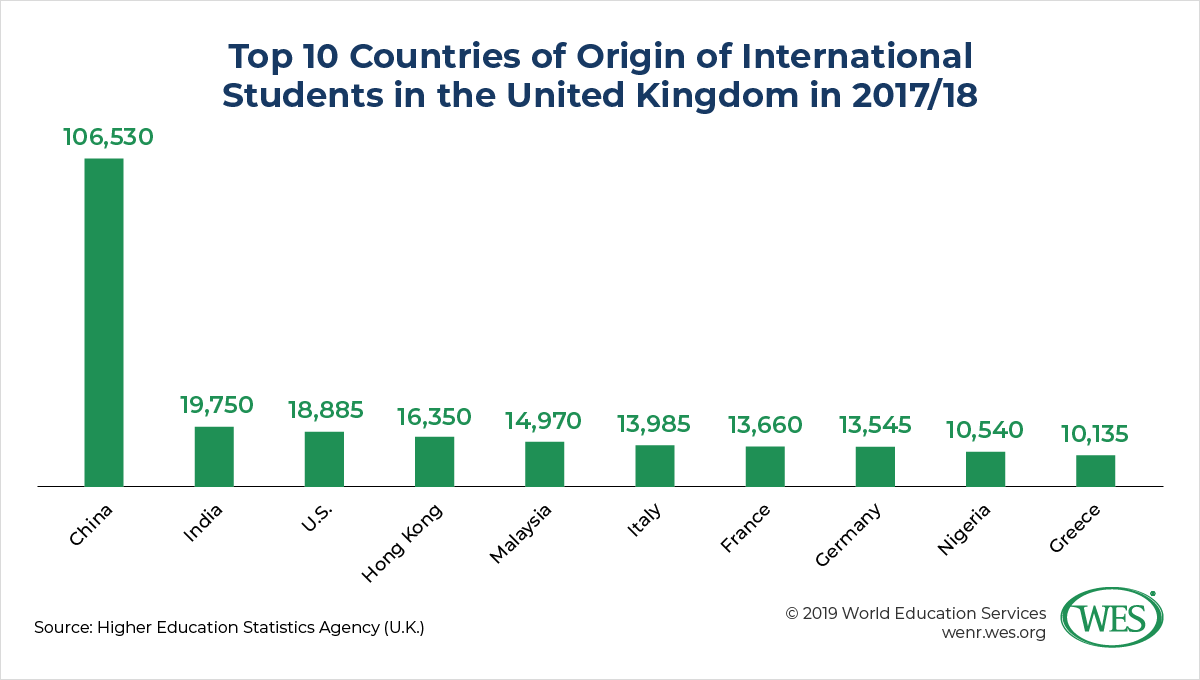

The United Kingdom

The picture in the U.K. is similar to that in other Western English-speaking countries. China is by far the largest sending country of international students; numbers are on an upward trajectory and rose from 87,895 in 2013/14 to 106,530 in 2017/18, as per U.K. statistics [82]. According to the Guardian, the “University of Manchester has the largest population of Chinese students in Europe. With about 5,000 Chinese students out of a total of just over 40,000, about one in eight students [is] Chinese [83].” Chinese students at the institution predominantly enroll in business and engineering programs with classes in these fields being particularly crowded with Chinese students. Aside from institutions like the University of Manchester, HEIs in London are also a top draw [84].

In addition, there are some 72,000 students enrolled in transnational programs and branch campuses of U.K. institutions in China [82]. Overall, offshore international enrollments in British transnational programs exceed the number of enrollments in the U.K. itself [85], but there are several countries with a greater market share than China.

[86]

[86]

Canada

Canada is yet another country that witnessed a massive surge in student inflows from China over the past two decades. In 2001, China overtook South Korea as the largest sending country of international students in Canada. Since then, the number of Chinese students in the country has jumped from 22,000 to 143,000 in 2018, according to federal government statistics [87]. Fully one quarter of international students in Canada now come from China, most of them clustered in cities like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal. By some accounts, “Chinese students make up nearly two-thirds of the international student body at the University of Toronto, more than one-third at the University of British Columbia and almost one-fourth at McGill University [88].” Notably, however, China is no longer the top sending country since there are now more Indian students in Canada than Chinese.

This inflow has multiple benefits for Canada. Educational services are among the country’s largest exports to China next to commodities. Overall, international student expenditures from all countries contributed $15.5 billion to Canada’s economy [89]. International students also make for formidable immigrants and help keep afloat Canadian universities and schools, many of which are under the pressure of demographic decline due to falling fertility rates [90]. However, as in other countries, there are now growing concerns that Canadian universities have become too dependent on students from just two countries—China and India. When the 2018 arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Canada sparked a diplomatic spat with China, the credit rating firm Moody’s Investors Service warned of potential financial risks for universities should China curtail student travel to Canada [88]. In response to such concerns, the Canadian government recently announced a new internationalization strategy that seeks to diversify Canada’s international student body [91].

Inbound Student Mobility

China is not only the largest sender of international students worldwide, it has over the past decade also emerged as a major destination country. According to government statistics [92], there were 492,185 international students from 196 countries in China in 2018—a remarkably high number globally. However, this number is difficult to compare with other data sources, such as UNESCO, which counts only tertiary degree-seeking students and doesn’t report numbers for China. The Chinese data, by contrast, also include high school students and students in various short-term vocational training programs, some of which last just a few days or weeks [93].

However, the government data reflect that there were 258,122 international students enrolled in degree programs, making China the world’s fifth leading destination country of tertiary degree-seeking students when compared with UIS data—an astonishing development few foresaw just a decade ago. Not only are Chinese universities seeking to boost their international enrollment quotas, the government has set an official target of 500,000 international students in China by 2020—a goal that appears within reach. While growth rates slowed to less than 1 percent [92] in 2018, there are now 227,000 more international students in China than in 2014 [94], and the government is ramping up spending to hit its recruitment target. Monies allocated to scholarships for international students increased by 20 percent [95] to USD$560 in 2018. China funded 63,041 international students that year.

These efforts are part of China’s drive to modernize its education system and become a key player in global higher education. They are also a part of China’s soft power strategy [96] in regions like Africa, where Chinese scholarships are embraced with open arms. But China’s appeal as a destination goes far beyond scholarships, given that no less than 87 percent of international students in China are self-funded.

As the number of English-taught programs offered by Chinese HEIs grows, studying in China increasingly affords students from developing countries an opportunity to obtain an education of better quality than at home at relatively low cost compared with Western destinations. Other students come to China to learn Chinese or establish contacts amid growing business ties with China. The country is also a major destination for medical education—a sector often underdeveloped and marred by capacity shortages in developing countries. For instance, 21,000 out of 23,000 Indian students in China were enrolled in medical programs in 2018. Given this surge in enrollments, the Chinese government recently authorized 45 medical colleges to offer programs in English [97].

Most international students in China—60 percent—come from Asia. The largest group of them is South Koreans, many of which are said to study in China to get an edge on the Korean labor market [98], seeing that China is South Korea’s largest trading partner. The second-largest group comes from Thailand, many of them Chinese Thais. Because of the boom in Chinese tourism in Thailand, many Thai students seek to learn Chinese to increase their employment prospects [99]. Other top sending countries are Pakistan and India, as well as the United States. A large number of U.S. students in China are enrolled in short-term study abroad programs [100] at the undergraduate level [101].

Of note, Africa has emerged as the second leading world region of international students in China in the wake of China becoming the continent’s largest trading partner and source of foreign investment. Between 2015 and 2018 alone, the number of African students in China spiked by 64 percent with Ghana being the leading sending country as of late [102]. Other sending countries include Nigeria, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. About 17 percent [92] of all international students in China now come from African countries.

[103]

[103]

……