课程思政

Exposition-Trends in Higher Education

2021-08-11

Source: Guide 2 Research

11 Top Trends in Higher Education: 2020/2021 Data, Insights & Predictions

in Research Posted on August 24, 2020

Author: Imed Bouchrika,

Universities and colleges are expected to impart marketable skills that prepare students for the dynamic world of work. To date, students continue to graduate and employers continue to hire new talent, and this has been the norm for centuries now. In the last two years, however, the skills gap has been widening at an alarming rate (SHRM, 2019), amidst the tightening career demands. Worse still, there has been a predictable change in student demographics, cultural environment, and entrepreneurial norms.

With these factors driving monumental shifts, more work needs to be done by learning institutions to ensure that graduates gain relevant knowledge and skills that better prepare them for the future of work (Inside Higher Ed, 2020). However, this is easier said than done, and universities and colleges alike have to remain abreast of the current trends in higher education to align their service with the job market while maintaining a leg-up on competitors.

This article aims to discuss the current social, technological, financial, and academic trends in higher education institutions across the globe to help both students, educators, and recruiters understand what changes to expect in the coming years. It provides a perspective on the higher education landscape as well as the key factors that will drive these changes in the industry.

Table of Contents

1. Diversity in Higher Education Students and Faculty

2. Increase in Non-Traditional Students

4. Embracing Artificial Intelligence for Learning

5. Online Learning is More Prevalent

6. Virtual Reality for Education

7. More Focus on Closing the Skills Gap

8. The Rise of Massive Open Online Course (MOOCs)

9. Enrollment of International Students

10. The Growing Need for Alternate Funding Options

11. A Changing Pathway For Fundraising Campaigns

Social Trends

Diversity in Higher Education Students and Faculty

Universities and colleges are tasked with promoting learners’ achievement and preparation for workforce competitiveness. Towards that end, institutions should strive to foster educational excellence and shrink opportunity gaps by creating welcoming and diverse campuses (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Besides, educators ought to recognize the educational value of ethnic and racial diversity and work towards breaking the barriers that inhibit proper diversification.

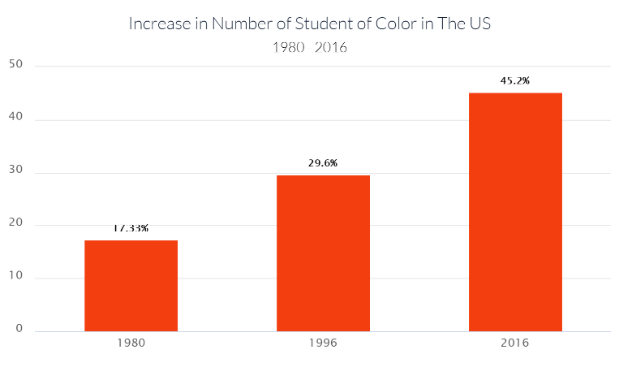

That being said, while many colleges and universities claim to have an articulated commitment to and mission for diversification, only a few devotedly walked the talk early on. To suffice, by the 1980s, students of color made up 17.33% of all undergraduate students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019).

In the 1990s, however, institutions of higher learning began to recognize the need to extend educational opportunities to students of all backgrounds. As a result, the number of students of color in the U.S. rose to 29.6% in 1996. Since then, this number has maintained an upward trend to reach 45.2% by 2016, which is a bold statement to the enhanced diversification efforts (American Council on Education, 2019).

Increase in Number of Student of Color in The US 1980 - 2016

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, American Council on Education

The growth is impelled by ongoing globalization and immigration, which have brought rich cultural elements and diversity to all sectors, including education. No more empty rhetorics. Every institution is now putting its best foot forward to achieve diversity, not just in terms of student communities but also administration. Diversity features can be utilized as an effective approach to guarantee a student population’s heterogeneity (Mahlangu, 2020).

Today, besides the growing number of students of color, 23% of higher education positions in the U.S. are held by racial and ethnic minorities (College and University Professional Association for Human Resources, 2020). The same intimates that racial and ethnic minorities are well represented in leadership positions in fiscal affairs (28%) and least represented in research/health sciences (11%). Moreover, today, women constitute 60% of higher education professionals, with their best representation coming in the academic affairs department (69%).

Increase in Non-Traditional Students

Traditionally, the terms “university student” and “college student” explicitly referred to 18- to 24-year-olds matriculated immediately after completing high school education (Hittepole, 2018). The society has for long presumed college students to be teenagers or young adults who lived with or were supported by their parents to make ends meet on campus. Age was the sole variable that emboldened the distinction between traditional and non-traditional students, at least until 2008.

As businesses took a hit during the Great Recession, many jobs were lost. According to a report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, approximately 4 out of 5 or 80% of jobs lost were held by employees without formal education beyond high school. (Carnevale et al., 2011).

From that point on, the importance of college education and the need to prepare for the future of jobs dawned on the workforce in general. Consequently, people who were juggling a host of responsibilities—full-time employees, parents, caregivers, and retirees—joined colleges and universities to reskill or upskill (Carnevale et al., 2011).

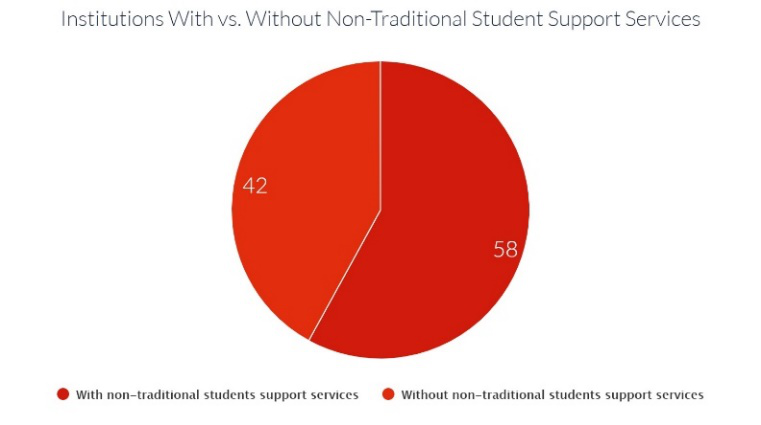

On the other hand, institutions altered their policies and models to help non-traditional students balance demanding schedules and competing priorities. The move further enticed more nontraditional students, and by 2015, 40% of undergraduate students at American universities and colleges were nontraditional (CLASP, 2015).

42 With non-traditional students support services

58 Without non-traditional students support services

Institutions With vs. Without Non-Traditional Student Support Services

Source: NASPA VPSA Census, 2014

This number is poised to keep the upward trend, thanks to the advent of programs, such as online program managers, online education, and MicroMasters programs, which are online graduate-level courses focusing on standalone skills.

Mental Health Awareness

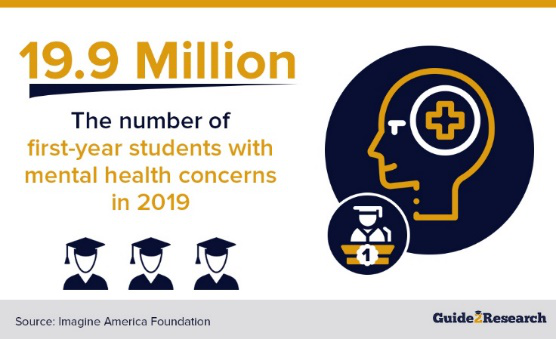

Experts use terms like “crisis” and “epidemic” to describe the lingering mental health challenges college students struggle with. The American Psychological Association backs this claim in a study on the prevalence of mental disorders amongst first-year students in eight countries, which revealed that 35% struggle with mental illness (American Psychological Association, 2018).

Further, a study by the National Center for Education Statistics shows that of the 20 million students enrolled in institutions of higher learning in 2019, 19.9 million had mental health challenges (Imagine America Foundation, 2020). Depression, eating disorders, anxiety, addiction, and suicide are some of the mental health issues today’s college students cannot shove aside. According to the American College Health Association (ACHA), 60% and 40% of students also suffered anxiety and depression, respectively (ACHA, 2019).

This challenge has compelled colleges and universities to come up with innovative approaches, online resources, and creative programs to increase mental health awareness. Institutions are dealing with the issues early on by proactively sharing mental health information with students during orientation sessions. Approaches used vary from panel discussions, role-playing, student testimonials, and short videos (University of Texas, 2016). Studies (see, for instance, Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010; Karwig et al., 2015) indicate that providing mental health interventions is found to be efficient in positively impacting the behavioral and emotional well-being of students (O’ Brien et al., 2020).

Additionally, some institutions such as Drexel University offer free mental health screenings to encourage students to monitor their mental health status and counter the stigma head-on. Using the slogan “get a checkup from the neck up,” the institution entices students to stop by the mental health kiosk for a quick series of questions. At the end of the private screening, students are given mental health support and resources, as needed (Rolen, 2015).

Technological Trends

Embracing Artificial Intelligence for Learning

The role of technology in higher learning is not only in equipping students with information but also in bridging access to quality education. It should help sidestep the constraints of time and location to promote lifelong learning opportunities for all while encouraging creativity, curiosity, and collaboration. One technology that brings an outsized potential to achieve these benefits for higher education is artificial intelligence (AI).

Since it entered the higher education realm, AI has stirred a buzz, thanks to the way it is transforming the methods of doing things in this industry. Understandably, there is a good deal of optimism that this emerging technology will automate and streamline workflows and processes that have been tedious and long.

Already, a number of universities and colleges are leveraging AI to offload time-sensitive academic and admin tasks, enhance enrollment, improve IT processes, and boost learning experience for students. For example, the Georgia Institute of Technology is using AI to lighten the duties of teaching assistants (Korn, 2016). The institution uses a virtual assistant called Jill Watson, to respond to consistently repeated questions posted by students in a masters-level AI class.

While AI holds an unfathomable promise for institutions of higher learning, its adoption in the education industry is still low (McKinsey Global Institute, 2017). A 2019 survey revealed that even though university leaders are aware of the significant role AI could play over the next 10-15 years, many are skeptical about its implementation. Studies show that only 41% of universities and colleges have a clear AI strategy in place. Also, cost remains a major impediment and it is, therefore, unsurprising that 57% of institutions have yet to allocate budget for AI projects (Pells, 2019)

Online Learning is More Prevalent

Online learning is a broad term that encompasses other modes of learning, such as blended learning and elearning. It is a subcategory of digital learning that simply means the use of online tools for learning. As Okojie et al. puts it, online learning is a form of learning that happens over the internet (Okojie, Mabel, & Tinukwa, 2020)

This type of learning takes place in non-traditional settings, enabling students to engage in learning, regardless of the constraint of time, distance, or location. In other words, the lecturer and the student do not have to be in the same room for learning to occur. The very nature of online learning, as well as technological advancements, explain the reasons why it is becoming so prevalent.

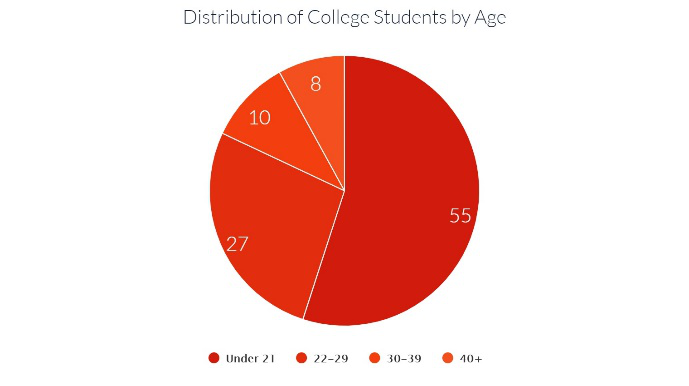

The latest statistics show that 55% of today’s college and university students are Gen Zers (Bil and Melinda Gates Foundation). The new generation of students are accustomed to using technology from a younger age and thus are comfortable at home using tech tools to acquire knowledge and skills. Pew Research reports that 95% of Gen Zers have access to smartphones, whereas 97% use at least one of the major online platforms (Parker & Igielnik, 2020).

Distribution of College Students by Age

Source: Bill &Melinda Gates Foundation

As such, the online landscape is well-known to today’s students, thus online learning is a proposition they inherently want to try. Currently, a third of higher education students are taking at least one class online. (Ginder, Kelly-Reid., & Mann, 2019).

Moreover, the advent of high-speed internet, which facilitates ubiquitous connectivity, gives online learning a boost. This, coupled with virtual communication and virtual reality technology means lecturers can deliver live online-only lectures to students in remote locations. The use of online-only courses has gathered momentum in recent months and it is poised to accelerate even after the COVID-19 dust settles.

Virtual Reality for Education

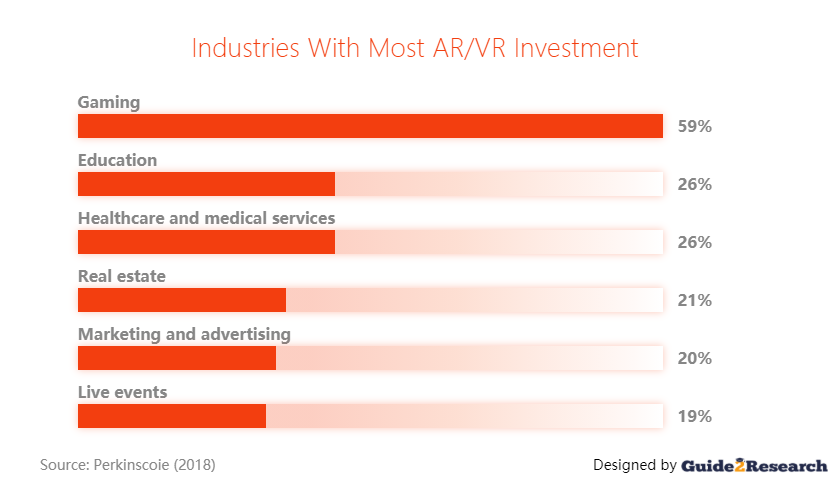

Virtual Reality (VR) is heralded by many as a game-changer in higher education. It is not a surprise, then, that the education sector was expected to attract the second most VR-related investments in 2018. (Perkinscoie, 2018)

As this immersive technology evolves, educators are increasingly looking into ways to incorporate VR into pedagogical approaches because of the benefits it delivers to students (Yu, Ally, & Tsinakos, 2020). Increased engagement and motivation, exploratory and contextualized learning, and experiential learning opportunities that may otherwise be inaccessible, are some of the affordances granted by VR. Using VR in deep learning, primarily in science and medical fields, triggers empathic responses that give students a perspective that has an enormous lasting impact.

Industries With Most AR/VR Investment

Source: Perkinscoie (2018)

Interestingly, these benefits are too mesmerizing to forego for 78% of higher education institutions. As of 2018, 18% of universities and colleges had fully deployed VR, 28% had used it to some extent, and 32% were testing the technology (Burroughs, 2018.; Internet2, 2019). These numbers are projected to grow rapidly in the coming years as more institutions jump on the bandwagon.

For example, Arizona State University uses VR to enable remote students to take part in lab exercises in an online biological science degree (Paterson, 2018). Other institutions using VR in higher learning include San Jose State University and the University of Illinois, among others.

Curriculum Trends

More Focus on Closing the Skills Gap

Mauricio Macri (former president of Argentina), while addressing the G20 summit in 2018 said “the future of work is a race between technology and education” (Accenture, 2020). Simply put, as technology advances, education systems should metamorphose, anticipate, and prepare for the impact of digital on the workforce.

That said, institutions of higher learning ought to focus on molding future employees by imparting knowledge, skills, and competencies that are demanded in the labor markets. For this reason, there is an urgent need to reimagine degree programs, courses, and curricula in general, to meet the needs of modern learners, while keeping pace with the evolving workforce (Educause Horizon Report, 2020).

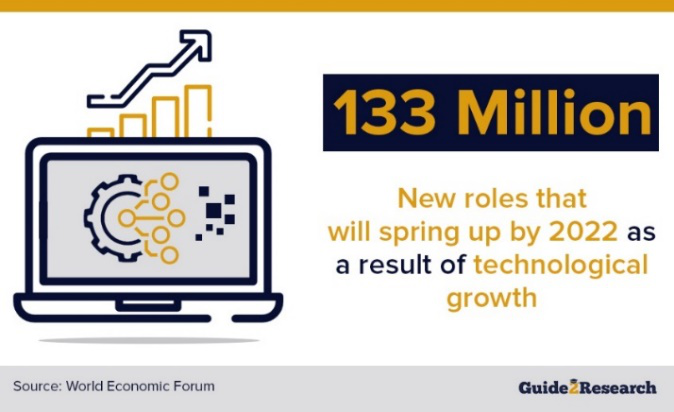

Primarily, the Fourth Industrial Revolution, impelled by the rapid advances in robotics, AI, and other emerging technologies have created skill gaps across all industries. More precisely, the division of labor between machines, algorithms, and humans is poised to generate 133 million new roles globally by 2022 (World Economic Forum, 2018). Likewise, the impact of technology-driven automation, the intricacies of job process, and the fragmentation of decision-making of the current workplace environment collectively result in the increasing skills demand across business sectors and industries (OECD, 2013, as cited in Wicht et al., 2019).

The race to solve the escalating skills crisis continues to take shape as institutions collaborate with corporates to devise the perfect remedy. Today, there is the rapid adoption of Corporate Partnership Programs within a centralized university’s career services departments (Davis & Binder, 2016). For example, Stanford University grants more than 40 corporate hiring departments direct access to its student pool (New, 2016).

Additionally, as the most relevant and useful blend of skills for each employee continuingly shift, Competency-Based Education (CBE) is gaining prominence. CBE helps institutions to address the needs of individual students and lays greater emphasis on broadening their variety of skills. Instead of measuring and incentivizing the macro-level output of the institutions, Universities such as Capella University and Western Governors University, have rebranded so-called learning outcomes as competencies. (Fain, 2019).

The Rise of Massive Open Online Course (MOOCs)

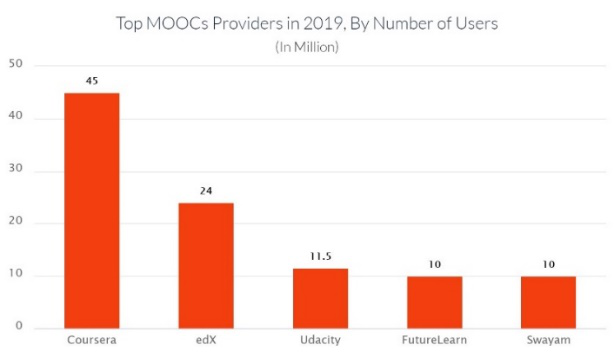

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are open online courses created for a large number of participants, provide free access, and can be accessed anytime, anywhere by anyone as long as they have an internet connection (Bernadas & Minchella, 2016). Building on the foundation of popular online courses, MOOCs have established a firm foothold in the education sector. Today, this revolutionary concept is reshaping the higher education model.

To better understand what has propelled this disruptive education model to its current stature, we must first understand the benefits of MOOCs. First, unlike traditional online courses, MOOCs come with the benefit of unlimited enrollment, fewer requirements, and are accessible on a global scale. Second, MOOCs are being offered at a minimal cost so they are the safest bet to turn the tide of overwhelming cost of education.

Another interesting fact is that MOOCs are not fixed into the traditional semester models of universities. This means students can start a course at any time and can be of any length. Better still, most of the courses are short and highly focused on a specific topic. This makes them a compelling prospect for learners who want to gain a deeper understanding of one area.

Top universities are increasingly launching MOOCs not only to stay ahead of the curve but also to improve access to education. In 2019 alone, MOOC providers launched approximately 2,500 courses, 170 micro-credential, and 11 online degrees. Overall, the MOOC movement has so far reached more than 110 million learners, excluding China (Shah, 2019). Companies such as Coursera, edX, Udacity, FutureLearn, and Swayam are partnering with leading institutions to solve the most pressing educational needs for modern students.

Top MOOCs Providers in 2019, By Number of Users

(In Million)

Source: Class Central

Enrollment of International Students

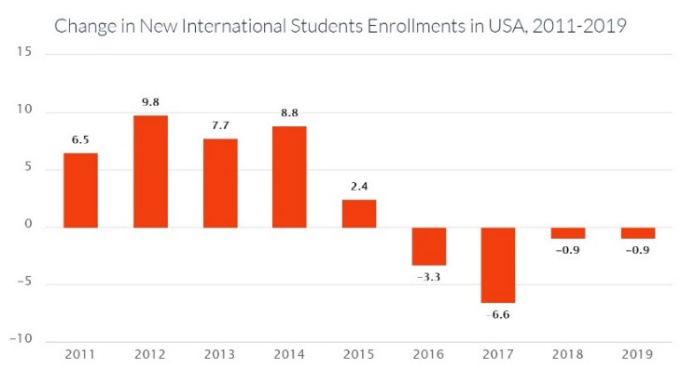

The decrease in the number of new students enrolling at U.S. universities is a trend that is gathering pace. In 2019 alone, 51% of institutions of higher learning in the U.S. recorded a decrease in the new enrollment of international students. On the other hand, 7% indicated no change, whereas 42% reported an increase (IIE, 2020).

Change in New International Students Enrollments in USA, 2011-2019

Source: Institute of International Education

In another report, IIE estimated the total decline in international student enrollment to be 0.9% in 2019. The failure to attract new international students by U.S. colleges and universities is a gain for institutions in other countries, such as Australia and Canada. Australia, in particular, has recorded significantly high enrollment rates—a 47% increase—between 2015 and 2018. (Australia Government Data, 2018).

What is to blame for this change? Among the factors that are driving this change include escalating global competition, social and political climate, high cost of higher education, and visa concerns in the U.S. Besides, the ban on Chinese nationals studying in America (Anderson, 2018), and the limited duration for Chinese students’ visas have contributed massively to the declining numbers of international students (BAL, 2018).

Financial Trends

A Changing Pathway for Fundraising Campaigns

According to a Giving USA report, the overall giving to institutions of higher learning decreased by 3.7% in 2018 (Giving USA, 2019). That is bad news. On the flip side, the total contributions to universities and colleges, increased by 7.2% to reach $46.73 billion. Besides, in the same year, seven institutions received at least one donation over $100 million, which is the largest number of institutions to hit that milestone since 2015.

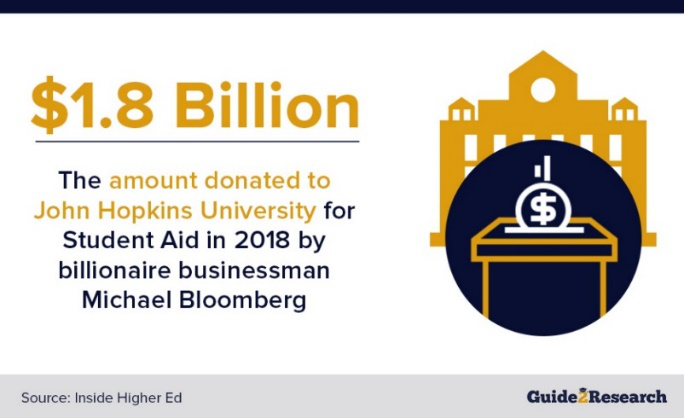

As huge capital campaign donations take an upward trend, donations from individual alumni have taken the exact opposite path. According to Giving USA, although the overall donation to institutions of higher learning is increasing, it is coming from fewer individuals (Giving USA, 2019). Michael Bloomberg’s historic $1.8 billion donations to John Hopkins University is the epitome of the changing pathway in giving (Benson, 2019). It signifies the start of a new trend where many donors have pulled out of giving, but the few that are ready to give are doing it so generously.

The Growing Need for Alternate Funding Options

Institutions of higher learning in the U.S. have been heavily reliant on federal funding. The exact amount contributed by each state towards this course can vary widely. According to a Grapevine report, the state’s fiscal support for higher education in 2019/2020 totaled nearly $96.6 billion, which represented a 5.0% increase nationwide from fiscal year 2018/2019 (Grapevine, 2020).

It turns out that this increase was just a smokescreen for some state leaders. For example, in Alaska, state funding decreased by a whopping 11.2%, owing to the state government’s decision to cut funding to the University of Alaska. Other states to record a decrease in state funding included Hawaii (2.2%) and New York (0.3%) (Grapevine, 2020). The decreasing funding from state governments has sent some school’s operations on a tailspin, forcing them to look elsewhere for funding.

Decrease in High Education Funding in Select States in 2020

As pressure to find financing mounts, public universities and colleges have gone back to the drawing board. The goal is to create initiatives that can pique the interest of businesses and private entities to fund learning. One brilliant idea has been to improve the faculty of research. A good example is Northeastern University, which has partnered with technology entrepreneur David Roux to launch a graduate education and research campus called The Roux Institute. Roux and his wife are funding the project with $100 million to help learners gain comprehension in the use of AI and machine learning (Northeastern University, 2020).

Keeping Up With the Changing Landscape of Higher Education

As you have read, the high education landscape is rapidly changing. The arena is being hit from all sides by social, curriculum, technological, and financial changes. Institutions that want to maintain a leg up on competitors and align better with their goal to produce “marketable” future employees should be prepared to adapt to these trends.

The changes witnessed in higher education have brought tangible benefits. For example, emerging technologies, such as VR have simplified learning, making it easily accessible to all learners, regardless of their location. Additionally, AI has enabled institutions to offer personalized learning to help learners gain the perfect blend of skills.

However, these technologies, in their current mode of application, are very expensive. For this reason, many institutions are unable to make the most of them. To work around this hurdle, universities and colleges should heavily invest in research to come up with innovative yet cheaper ways to adopt emerging technologies.

The technologies aside, more research is needed to determine what curriculum will work best for future learners. Moreover, stakeholders ought to engage the government and iron out issues that are causing a decline in the number of international students. Besides, as the number of nontraditionals continues to soar, universities should double down on providing better support services.

References:

1. Accenture. (2020). It’s Learning Just Not As We Know it. Dublin, Ireland: Accenture.

2. ACU (2019). Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

3. APA (2018). World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and Distribution of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

4. Anderson, S. (2018, October 18). What will Trump do next with Chinese student visas? Forbes.

5. BAL Global. (2018, May 30). State Department announces new restrictions on visa validity for some Chinese nationals. BAL Global.

6. Benson, M.T. (2019, January 17). Michael Bloomberg: Channeling His Inner Johns Hopkins. InsideHigherEd.

7. Bernadas, C., & Minchella, D. (2016). ECSM2016-Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Social Media (pp. 96). Reading, England: Academic Conferences and Publishing International. Google Books

8. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (n.d.). Today’s College Students. Seattle, WA: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

9. Brereton, E. (2019, August 1). Virtual Reality in Higher Education: Elevating the Transfer of Knowledge. EdTech Magazine.

10. Burroughs, A. (2018). UBTech 2018: Higher Ed Sees Great Potential in Virtual Reality. EdTech Magazine.

11. Carnevale, A.P., Jayasundera, T., & Cheah, B. (2011). The College Advantage Weathering Economic Storm. Washington, DC: Georgetown University.

12. CUPA-HR (2020). Professionals in Higher Education Survey. Knoxville, TN: College and University Professional Association for Human Resources.

13. Davis, D., & Binder, A. (2016). Selling students: The rise of corporate partnership programs in university career centers. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 46, 395-422. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X20160000046013

14. Digital Marketing Institute (n.d.). What Will Higher Education Look Like in 2020? DMI

15. EDUCAUSE (2020). The Horizon Report. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-horizon-report-trends.

16. Fain, P. (2019, January 28). Slow and steady for competency-based education. InsideHigherEd

17. Ginder, S.A., Kelly-Reid, J.E., & Mann, F.B. (2019). Enrollment and Employees in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2017; and Financial Statistics and Academic Libraries, Fiscal Year 2017. Washington, DC: NCES.

18. Giving USA, (2019, June 18). Giving USA 2019: Americans gave $427.71 billion to charity in 2018 amid complex year for charitable giving. Giving USA

19. Grapevine. (2020). Annual Grapevine Compilation of State Fiscal Support for Higher Education Results for Fiscal Year 2020. Illinois State University

20. Guidry, L. (2018, October 3), Older students are the new normal at college. The reason? The recession and new technology. USA Today.

21. Hittepole, C. (2018). Nontraditional Students: Supporting Changing Student Populations. NASPA

22. Imagine America Foundation, (2020, March 2). Health of U.S. College Students: Part I. Imagine-America

23. Institute of International Education. (2019). Fall 2019 International Student Enrollment Snapshot Survey. IIE.org

24. Mahlangu, V.P. (2020). Rethinking student admission and access in higher education through the lens of capabilities approach. International Journal of Educational Management, 34 (1), 175-185. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2019-0135

25. McKinsey (2017, June). Artificial Intelligence: The Next Digital Frontier? McKinsey Global Institute

26. National Center for Education Statistics (2019). Total undergraduate fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by attendance status, sex of student, and control and level of the institution. Washington, DC: NCES.

27. New, J. (2016, July 5). Career counselors or headhunters. InsideHigherEd

28. O’ Brien, N., Lawlor, M., Chambers, F., & O’Brien, W. (2020). Mental fitness in higher education: Intervention mapping program design. Health Education, 120 (1), 21-39. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-09-2019-0042

29. Okojie, Mabel, C. P. O., & Tinukwa, C. (2020). Handbook of Research on Adult Learning in Higher Education (pp. 344). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference/IGI Global. Google Books

30. Parker, K., & Igielnik, R. (2020, May 14). On the cusp of adulthood and facing an uncertain future: what we know about Gen Z so far. PewSocialTrends.

31. Paterson, J. (2018, August 28). Arizona State online biology students getting hands-on experience in virtual labs. EducationDive.

32. Pells, R. (2019, March 28). The THE-Microsoft survey on AI. London, UK: TimesHigherEducation.

33. PerkinsCoie. (2018). 2018 Augmented and Virtual Reality Survey Report. Seattle, WA: PerkinsCoie.

34. Rolen, E. (2015, June 25). Drexel University implements new mental health kiosk. USA Today

35. Shah, D. (2019, December 2). By the numbers: MOOCs in 2019. ClassCentral

36. The University of Texas. (2016, April 21). University leads statewide task force to create suicide prevention video. UT News.

37. Thomsen, I. (2020, January 27). Northeastern University partners with entrepreneur David Roux to launch the Roux Institute of Northeastern in Portland, Maine. News@NorthEastern. Boston, MA: Northeastern University.

38. US Department of Education. (2016, November). Advancing Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education. Washington, DC: Department of Education.

39. Wicht, A., Müller, N., Haasler, S., & Nonnenmacher, A. (2019). The Interplay between education, skills, and job quality. Social Inclusion, 7 (3), 254-269. https://dx.doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i3.2052

40. WEF. (2018). The Future of Jobs Report 2018. Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

41. Yu, S., Ally, M., & Tsinakos, A. (2020). Emerging Technologies and Pedagogies in the Curriculum (pp.170). New York, NY: Springer. Google Books